By Ray Sawhill

You don’t turn to Ishmael Reed’s fiction for fully-rounded characters in whose detailed and textured world you lose yourself only to re-emerge refreshed and renewed. You turn to it for zig-zaggy energy, iconoclastic brains, and freaky satire. Novels such as “The Free-Lance Pallbearers” and “Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down” — if those titles make you smile, you’ll probably enjoy the books — are less likely to call to mind comparisons with “Middlemarch” than they are with “Krazy Kat,” R. Crumb, and “Richard Pryor Live in Concert.” They’re like underground comix for the literary audience.

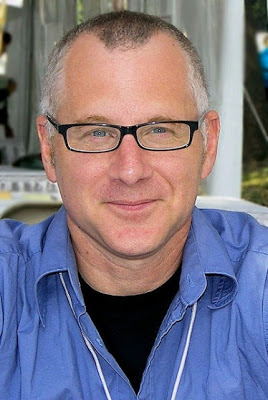

Reed, perhaps the premier trickster figure of current American letters, is a whirlwind of industry and deviltry. He has written plays, as well as volumes of poems and essays, and has founded small magazines and a prize-awarding literary organization, the Before Columbus Foundation. Although generally well-reviewed, and turned to by the media for his reliably corrosive observations and commentary, he has seldom gotten the credit he has earned as a literary innovator. (It’s the fate of humorists not to receive the recognition they deserve for their achievements as technicians, let alone artists.) In “Mumbo Jumbo” (1972), for instance, Reed mixed up fictional and historical figures, and spliced newsreel and fantasy elements into his story lines, three years before E.L. Doctorow was lauded for doing similar things in the smoother and more polished “Ragtime.”

Usually at his best in short bursts of invention and ridicule, Reed may be more valuable as a provocateur than for any of his individual works, some of which are reminders of how exhausting and antic ’60s-style writing can be. And recently his attitudes have taken a more earnest, and more predictably multicultural, turn than his fans might prefer. (It’s a lot more fun watching Reed go nuts than it is learning what he actually believes.) But when he’s on his game, no writer has been better at conveying how crazy, man, crazy our racial jambalaya can render a soul. His most sustained performance, and the best place to start, is “Escape to Canada,” in which he plays harlequin changes on the traditional slave narrative.

- Buy some of my favorites: “Escape to Canada“; “Mumbo Jumbo“; “The Free-Lance Pallbearers.”

- Ishmael Reed’s website.

- A Paris Review interview with Reed.

©1999 by Ray Sawhill. First appeared in The Salon.com Reader’s Guide to Contemporary Literature.